So you might be reading the title of this post and be thinking, "Greenwich Village? What's an ecologist going to do there?" Turns out, a lot. Georgia Silvera Seamans has been on my radar for a couple of years via her thoughtful and meticulously researched blog the local ecologist, where she writes about her life as a nature lover in New York City. Specifically, she writes about her neighborhood park, the iconic Washington Square Park (WSP), and the goings on of the flora and fauna that live within it. So besotted was she with the park that she co-founded WSP Eco Projects , a non-profit with the purpose of educating visitors about the natural history of this very urban open space.

Georgia comes to this role with some heft: She's an urban forestry consultant with a PhD in landscape architecture and environmental planning from University of California, Berkeley and a Masters in environmental management from the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. Her 15 year career covers trees, the life those trees support, and the urban settings where those trees cohabit with people.

As an urban gal myself, the stories Georgia tells ring familiar to me: we both seek and revere nature in place, and want to share it with our fellow city-dwellers. In her blog and through WSP Eco Projects, Georgia brings an intimately-focused study to life for visitors to the park. She peels away the layers of city sheen to share everything from insects to fungus to leaves and root patterns, all found in her park around the corner.

And more recently, she's focused on the birds of the park. In WSP's modest 9.75 acres, Georgia and her colleagues have recorded a whopping 57 bird species since starting the census in 2016 (and according to eBird records, 87 species have been seen). Such dedication to a small urban park as an educator and advocate really impresses me. I wanted to learn more about Georgia and her projects so invited her for an interview here.

How did you develop a passion for trees and the life trees support?

Georgia Silvera Seamans: I was born in Jamaica and lived there until I was 13. In growing up, we had fruit trees and played in them and ate from them. The development where we lived was converted from sugarcane, and there were undeveloped lots where we could explore. Jamaica is a good mix of landscape types--coastline, then more dense vegetation inland. I thought everyone had access to this kind of environment. When we moved to the US I realized not everyone can walk outside and pick fruit!

Later my passion for trees solidified in grad school, when I was studying environmental law and policy. My classes had an urban focus, being in New Haven, and after graduating I served as a forestry intern for the city. That set me on this path of urban forestry focus.

Who supported your interest in trees and urban forestry? Who are your role models? Do you encounter many other people of color in your field?

GSS: My mom has always had a green thumb and interest in plants. I'm drawn to people and plants; it's a non-discriminatory area of activity. I had mentors at Yale, as well as within the portfolio of community groups I worked with as part of my graduate studies. All of these groups were led by black women and many people of color volunteers, many of them older people, dedicated to thriving green spaces in an urban setting.

There was not a lot of domestic diversity in my graduate program at Yale, though there was international diversity. Yale recognizes this and is trying to remedy the lack of diversity. But it may be a reflection of the New England location. For instance I know there are many students of color studying forestry in the South (of the US).

Urban forestry is a component of social justice and much of that work is being done by people of color. Issues like storm water and air pollution impact those living in the city. I think about the professional pipeline and getting kids of color to think about urban forestry as a viable profession. It's easier to engage a young person if that person looks like them. But I do not feel like a trailblazer. There are many people doing this work already, and people like Wangari Maathai in Kenya; they are my role models.

Washington Square Park in early spring. Photo by Georgia Silvera Seamans.

What led you to found WSP Eco Projects?

GSS: I live very close to the park and wanted to share information about its trees with other visitors. Four years ago another park enthusiast Cathryn Swan and I combined forces and applied for a grant through In Our Back Yard to create a Tree Map of Washington Square Park. Casey Brown was the developer of the map, and its creation inspired me to design more educational programming around the park.

WSP Eco Projects is the name of this offshoot idea; I wanted the name to be nimble enough to allow a variety of things for and of the park. We are not a formal 501(c)(3) but I hope to be one day. We're permitted by the City of New York, which allows us to lead walks and other programming, and we follow research protocols for any data we collect in the park. These things give us legitimacy and makes our data valid and something we can offer to scientists.

We're all volunteer run and those leading walks or projects donate their time and expertise. We have a core group of us and want to grow, but it's NYC and people are really busy! Our model is more intermittent participation, asking people for a once a year donation of time. For instance, Heather Wolf of The Birds of Brooklyn Bridge led a few walks for us and has indicated an interest in working together again. We take advantage of things that come our way and try to offer plant and bird walks seasonally.

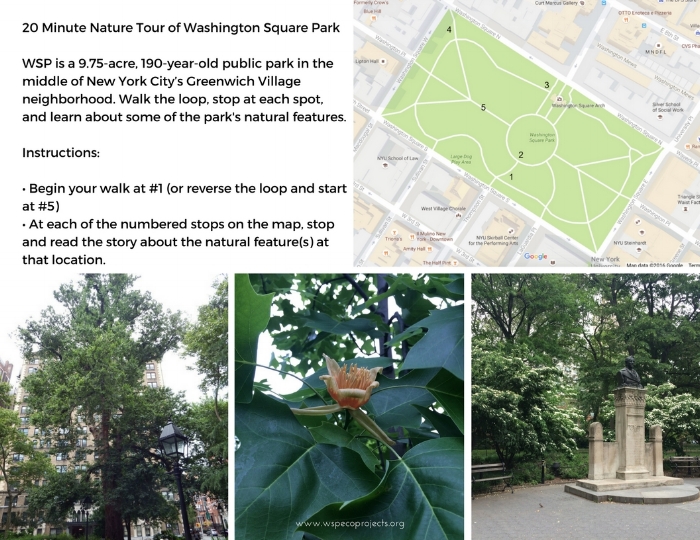

Interpretive hand out developed by the WSP Eco project for a tour of the park's trees. Courtesy of WSP Eco Project.

The flip side of the interpretive hand out.

I've noticed you are writing a lot more about birds in the park; that's something that clearly resonates with me as an urban bird advocate.

GSS: My mentor for birding is Loyan Beausoleil, who is responsible for the success of the bird survey of the park, which was started in August 2016. We count birds as part of a larger vertebrate survey including squirrels and rodents. We conduct the survey under the auspices of a permit issues by the NYC Parks Natural Resources Group. We record species and number of individuals observed along a roughly 1/2 mile transect. Eco Projects has observed 57 species between 2016 and present using this transect model.

The most unusual bird we’ve seen since the survey began was a Kentucky Warbler in May 2017. In addition to the survey, Loyan and I bird separately in the park. Lately there have been Wood Thrush, Swainson’s Thrush, Hermit Thrush, Ovenbird, Gray Catbird, Common Yellowthroat, Black-and-white Warbler, a Scarlet Tanager, and today, I saw an American Redstart. A birder in the park recorded a Chestnut-sided Warbler over the weekend. Finally, there are three eyases in the redtails’ nest this year. The nest has been in the same location since 2011, on a 12th floor window ledge of the NYU Bobst Library.

As a result of our survey, we wanted to bring bird education materials to WSP in the spring and summer. We partnered with the Uni Project to create a pop-up learning environment within the park, and with them applied for a Blake-Nuttall grant (which supports bird-related projects in New England). The collaboration is called EXPLORE Birds, and is a simple intro to any bird you will see in New York City.

Now, we have skins and books about birds, and the collection is growing as we speak. I applied for federal and state permits to possess bird biofacts for educational purposes for WSP Ec-Projects. Loyan and I are learning how to prepare skins at the American Museum of Natural History. All the birds are window or car strikes. We have two kestrels, a northern flicker, red-tailed hawk, pigeon, and starling skins.

We've now taken Explore Birds to other neighborhoods. We participated in April Earth day block party in Brooklyn, and I was blown away by the enthusiasm we got. Especially the children, who were like bees to honey over the bird skins. They were delighted by the display, and to learn that the skins (starlings) they were handling had live counterparts in the plaza. It was three hours of nonstop interest at our table.

It's not until it's pointed out, sometimes, that people see and hear what's always been there.

GSS: The way that people interact with their environment, not all people are at the same place you are on the spectrum. And that is sometimes where outreach fails. Hearing people's story, everyone has a story about birds. The way we talk about science is different for every community. People use different language to talk about the same things, and may know as much as you do when talking to your peers.

Georgia at an Earth Day event in Brooklyn, April 2018 at the EXPLORE Birds booth. EXPLORE Birds is a partnership between Eco Projects and the Uni Project. Photo credit: The Uni Project.

A close up of the bird skins at the booth. Photo credit: The Uni Project.

Have you explored "true" wild spaces around the world, larger intact ecosystems? Where?

GSS: I smiled broadly when I read this question. I know what you mean by this question but in my work with Eco Projects I try very hard to convince people of the wild/wildness in the park.

I’ve spent time in capital N nature. When I lived in California we hiked and camped in Yosemite and Kings Canyon. We visited Point Reyes National Seashore and the wide open spaces in wine country. After college, I volunteered with Ameri Corps and spent time in big landscapes Oregon and in Idaho. In college, I studied abroad in Botswana and as part of that experience, we spent a lot of time in the bush with some of the most well-known charismatic mega fauna.

What about cities outside the US? What is your observation of urban forestry outside the US?

GSS: Interesting that you should ask this question. I am not very familiar with urban forestry outside the US but I was talking with a friend recently about tree planting in cities. She’s from Russia and she has observed that NYC and US cities in general don’t have a lot of trees. There are not the tree-lined streets or boulevards that she’s used to. In addition to Russia, she’s lived in Germany and Japan and she’s noted that the green spaces in those countries are more heavily treed and more numerous and accessible.

In addition to the anecdote from my neighbor I would say that there are a few things happening in abroad in Europe that I've been following that maybe not explicitly urban forestry fall into broader study of urban ecology.

1 - The successful campaign to begin the process of making London the first National City Park;

2 - Expanding the traditional conception of ecosystem services has shone a light on the relationship between health and urban green space. Health is hot spot in the conversation and research about the benefits of urban green spaces. Access to green space is implicated in cognitive, behavioral and general mental health outcomes across age groups. Florence Williams in her book The Nature Fix profiles several international programs designed to take advantage of nature's wellness benefits.

In the U.S. Dr. Frances Kuo has an excellent portfolio of research on the benefits for children who have access to green space. Check out her lab: http://lhhl.illinois.edu/about.htm. More recently, Dr. Robert Zarr designed and launched the Park Rx program in DC. I heard him speak at a meeting of the Sustainable Urban Forest Council.

3 - Elevating the status of spontaneous vegetation. A lot of this work is being done by artists, designers. It's also happening here in the U.S. too. My research on US and European artists/designers was published recently. I think this is linked to conversation about what vegetation will thrive in climate-changed cities and regions.

What about YOU and your professional goals--where do you see yourself in 10 years?

GSS: I see myself still engaged with Eco Projects. This is a passion project for me but it’s also something that I would like to continue to professionalize. I would like to operationalize the model so that other parks can use the framework for education, advocacy, and research. My early professional background is in urban and community forestry.

Over the last couple of years I’ve gotten into birding and would imagine that I would have progressed in bird ID and biology in 10 years. I’d also like to be gainfully employed as a writer, telling stories about people and their relationships to the nature of cities.

The group at WSP for the 2018 Great Backyard Bird Count in February. Georgia is second from left. Photo by Heather Wolf of The Birds of Brooklyn Bridge.

This interview was conducted over the phone and by email in April, 2018. Some portions have been edited and condensed for clarity.