Who doesn't think bird banding is about the coolest job in the world? It's a skill so specific that one must be trained to do it, so there's a bit of bragging rights for anyone with access, reason and the facility to set nets and hold a bird in the hand.

And this is bird banding for science, guys, that should to be obvious to anyone reading this blog. I advocate conservation and the bird banders featured here are part of formal bird monitoring programs. So not only is bird banding itself mind-blowingly cool to imagine as one's job, but it's also for the greater good. These banders are monitoring bird populations in threatened ecosystems, and contributing to sustained and potential conservation of habitat where they work.

I found both featured gal bird banders on Instagram, where their respective accounts feature their travels and close ups of banded birds, a lifestyle exhilarating to me as an observer of birds from afar. Their images do not tell the whole story of how and why they came to this romantic-seeming life of bird banding, so I approached both of them to get their stories.

The first bander is Kylynn Clare, 26, from Salt Lake City, Utah. She has a bachelor's degree in Avian Ecology and Conservation Biology from the University of Utah, where it was she got her banding chops. Kylynn's photos from Turkey caught my eye, which is where she most recently did field work. She worked at a field station in the northeastern corner of the country, near the border with Armenia. Her photos during this time capture not only the birds but country-specific cultural moments. Her judicious use of filters (and occasional hair color changes) added to the magical (if not exactly "true to life," but that's OK!) feel of her feed.

We emailed and Face Timed over several weeks in June 2018 and below is her interview.

Clare and a Western Kingbird, Red Butte Canyon, Utah.

How did you become a bird bander?

Kylynn Clare: I started working in The Ecology and Conservation Biology Lab through the University of Utah (U of U) six years ago, when I was about 20 years old, a sophomore in college. I wanted research opportunities in a lab on campus that dealt with wildlife research, hoping to start getting some experience. My first job there was entering and analyzing point count data collected over 25 years of field work in Red Butte Canyon near campus.

The lab was run by assistant professor in the Department of Biology (and National Geographic Explorer) Cagan Sekercioglu. At one point he asked me to check out the bird banding station in Red Butte Canyon so I could get some field experience. As soon as I held a bird in the hand I was hooked. It truly is magical being able to see these amazing creatures up close. I believe my first bird was a male Lazuli Bunting.

Ever since, I’ve been working towards achieving a master banding permit through the North American Banding Council (NABC). At one point I was sub-permitted through the NABC under Cagan but that permit is expired now (it only lasts two years).

The sky over Aras station, Turkey.

How did you end up in Turkey?

KC: I ended up in Turkey through the same mentor from my U of U days. I've been bird banding through his lab at multiple stations since the beginning. Once I graduated in 2016 I wanted to continue working with birds in the field and so, after a couple years of bird banding in Red Butte Canyon and leading the Rio Mesa Bird Banding Station in Moab, Utah, I asked him of potential volunteer opportunities to band in Turkey.

He was happy to have another "ringer" (as they say in Europe) join the team and help out around the station. I arrived here at the Aras River Bird Ringing Station near Tuzluca, Turkey in late March and have worked every day, for 12 hours a day, ever since. The banding station is in this specific location because of the Aras river, which is like a bird highway on the migration route. The area is a source of food and water for birds, so the bird density is high in the spring. This area is in danger of development for a dam, so the station and the bird census data is valuable in preventing that.

Eurasian Nightjar.

Most bird banding stations receive very limited funding, if any at all. Generally they are run by small non-profit organizations or private donors, like this one. I have been volunteering since the beginning as I am still developing the skills I need to begin a career in this field. I am generally provided housing, and sometimes food, which is all I really need to make it through a full season of work and it’s what I’ll continue to do until I can begin getting paid.

The station house where the banders lived during the season.

Describe a typical day.

KC: We'd get up at 4:30 am and walk to the station which was about one kilometer away. We'd release the birds from the previous night and also do a morning net check. We'd be pressed for time because you can't let the birds stay in the nets for too long; they could be eaten or they could hurt themselves struggling to free themselves. Usually there were enough of us ringers to get the job done and then we'd reset the nets and start our 12-hour day. It goes something like this: net check every hour, bring birds to the banding area, a trailer set up with all our gear. We care about getting the birds out of the net and banded, then released, as quickly as possible. And there is motivation to catch at dawn and dusk, since that's when birds are most active.

We'd also do outreach from the station. At the end of the season we brought the trailer back to the house where we stayed. I leave in about a week, which means I have been living and working here for about three months.

With fellow ringer Berkan Demir, and a Common Nightingale.

What did the outreach look like?

KC: The Aras Ringing Station is operated by Kuzey Doga (which translates to North Nature Society ) and is well known in Turkey. TV crews would stop by during the season. Also groups of students. We'd do presentations for them, but they did not do net runs with us. Kids from the area also stopped by out of curiosity. The outreach we did was in place.

Being interviewed by a Turkish TV crew.

What's your most memorable birding banding experience so far?

KC: My most memorable moment banding here in Turkey is when I processed my first owl species, a Eurasian Scops Owl, on the day I turned 26. Owls are my favorite raptors and I was beyond excited to finally have one on my species list of banded birds. This particular bird reminded me of the Western Screech Owl, my favorite North American owl species, so it was something new that reminded me of home some 8,000 km away.

Eurasian Scops Owl.

Of course, that wasn't the only memorable moment. Another was when we re-trapped a Sand Martin, or Bank Swallow, that had originally been banded in Tel Aviv, Israel as a juvenile four years ago. That means this particular bird has migrated to Africa eight times and flown over 10,000 kilometers. I was absolutely stunned by this information. I'm sure there are countless more individuals who have accomplished this feat, we just don't know it. This is another reason why bird banding is important. Without it, we would never know any details about the lives of individual birds such as this Sand Martin.

Sand Martin/Bank Swallow.

What is your observation of bird conservation in Turkey? How many country nationals and women are involved in this work?

KC: Turkey is a developing, second world country. That means their economy is certainly more developed than a third world country but has not quite reached the status of a first world country, like the United States. This being the case, there aren't as many rules and regulations that protect wildlife as there are in the US. This is why it is especially important to continue bird banding research and outreach here. Not only does this outreach help the birds, but it helps other wildlife that live in the habitats here: such as bears, wolves, boars, foxes, multiple amphibian and reptile species, and many many more plants and invertebrates.

At the station there are several people of many nationalities, mostly from Europe and the Middle East, and as I understand many more that have worked here in the past. There is a close balance of men and women volunteers, however the number of female ringers and biologists are outnumbered. I've only been here for one season, and I'm sure there have been women scientists that have been here before, but as far as I know I am one of very few women that have lived and worked here for a full season.

We even had a kid volunteer this season. He was part of a family from Belgium who came to volunteer for a week as their vacation! I was impressed by that.

Wearing a head scarf.

How do you manage the itinerant lifestyle?

KC: I've signed up for it. It's about doing the job for a season versus being in an office.Three months goes by really fast. I work at a restaurant back home in between seasons, and nothing changes at home. From living in the field to going back to "real life" is crazy. But it's not really sustainable way to make money. While I am getting the experience I need to apply to paying jobs, I'll travel the world as much as I can. I like living in new places and cultures. In Turkey I couldn't wear shorts, and I just conform to the norms. I'm also researching graduate school programs.

Is it lonely work?

KC: You make good friends, but you're most likely not going to see them again. I dated a fellow bander for three months in Turkey and now we're seeing how that's going to work, since I am back home and he's in Turkey. Technology makes keeping in touch easier, but everyone's busy. It's kind of lonely but it's the life I chose. I'll enjoy it while I can, and everyone else kind of operates this way too.

Where are you headed next?

KC: Through the lead ringer here, I got in touch with some birders in Tel Aviv, Israel at the same bird banding station where the badass Sand Martin was first banded. After looking through my Instagram photos and eBird checklists they asked me if I would be interested in coming to the station to "ring" for the fall. Of course I didn't hesitate to say yes.

Tel Aviv is a very special place because it is one of the last stopover spots for migrating birds before they cross the Sahara Desert, an ocean of sand 9.2 million square kilometers large and 4,800 kilometers from North to South.

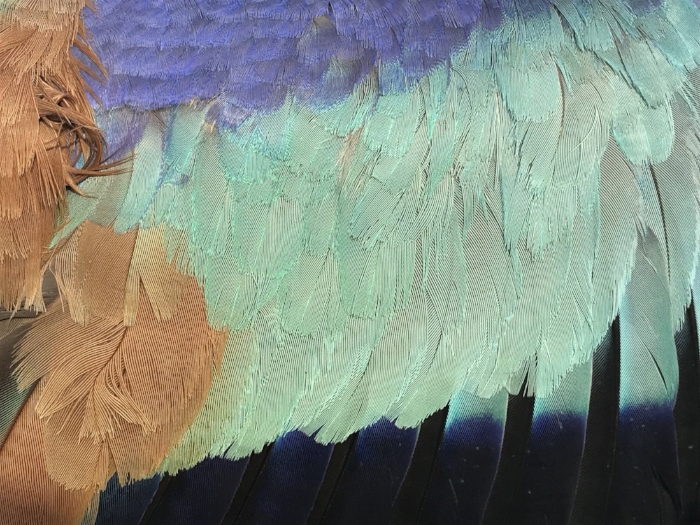

Close up of a European Roller plumage.

I want to stay in bird conservation and field work and I'm researching graduate school programs. Despite the early hours, lack of sleep, and hard physical labor in various weather conditions you cannot beat the excitement and adventurous aspects of this work. It is my passion, and I want future generations to enjoy the natural world as we know it now. I want to help protect what we have left and field work is the first step in making it happen.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.